Our article on how a huge expansion of the human niche in Africa around 70,000 years ago likely equipped later out-of-Africa dispersals with unique ecological flexibility is now published in Nature.

Emily Y. Hallett, Michela Leonardi, Jacopo Niccolò Cerasoni, Manuel Will, Robert Beyer, Mario Krapp, Andrew W. Kandel, Andrea Manica & Eleanor M. L. Scerri

Major expansion in the human niche preceded out of Africa dispersal

Nature

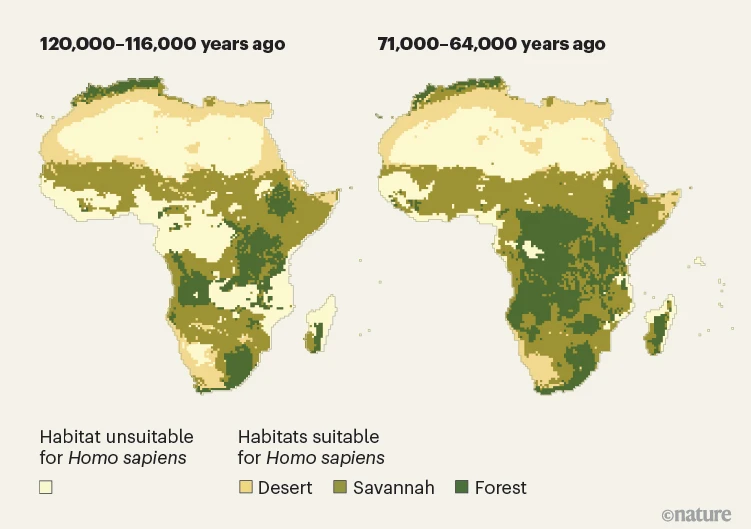

Homo sapiens evolved in Africa starting around 300,000 or 250,000 years ago. Despite having attempted dispersals out of Africa several times during this period, all non-Africans today descend from a single dispersal that happened around 50,000 years ago.

In this article, we reconstruct human ecological dynamics in Africa between 120,000 and 15,000 years ago, using the method we developed for our study on ungulates. We found that humans began to occupy new environments around 70,000 years ago. Because this occurred in quite different habitats at the same time, it is unlikely to be due to a single technological innovation (e.g., for storing and transporting water).

The most likely explanation is that during this period, positive feedback occurred between larger geographical ranges, increased contacts between populations (as also suggested by morphological data), facilitated cultural exchanges, and a higher likelihood of developing and maintaining innovations.

This increased ecological flexibility would have later helped humans successfully disperse out of Africa.

Article

Emily Y. Hallett, Michela Leonardi, Jacopo Niccolò Cerasoni, Manuel Will, Robert Beyer, Mario Krapp, Andrew W. Kandel, Andrea Manica & Eleanor M. L. Scerri

Major expansion in the human niche preceded out of Africa dispersal

Nature

Abstract

All contemporary Eurasians trace most of their ancestry to a small population that dispersed out of Africa about 50,000 years ago (ka)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. By contrast, fossil evidence attests to earlier migrations out of Africa10,11,12,13,14,15. These lines of evidence can only be reconciled if early dispersals made little to no genetic contribution to the later, major wave. A key question therefore concerns what factors facilitated the successful later dispersal that led to long-term settlement beyond Africa. Here we show that a notable expansion in human niche breadth within Africa precedes this later dispersal. We assembled a pan-African database of chronometrically dated archaeological sites and used species distribution models (SDMs) to quantify changes in the bioclimatic niche over the past 120,000 years. We found that the human niche began to expand substantially from 70 ka and that this expansion was driven by humans increasing their use of diverse habitat types, from forests to arid deserts. Thus, humans dispersing out of Africa after 50 ka were equipped with a distinctive ecological flexibility among hominins as they encountered climatically challenging habitats, providing a key mechanism for their adaptive success.

Media coverage

New York Times: “When Humans Learned to Live Everywhere” by Carl Zimmer

The Independent: “Early humans adapted to extreme habitats. Researchers say it set the stage for global migration“

New Scientist: “70,000 years ago humans underwent a major shift – that’s why we exist” by Michael Marshall

Nature News and Views: “Homo sapiens adapted to diverse habitats before successfully populating Eurasia” by William Banks

Natural History Museum: “Sharing ideas might have helped Homo sapiens adapt for life outside Africa” by James Ashworth

University of Cambridge: “Learning to thrive in diverse African habitats allowed early humans to spread across the world“

IFLScience: “Why Homo Sapiens Failed To Migrate Out Of Africa Until 60,000 Years Ago“

Naked Scientist: “Humanity’s road to dominance began earlier than expected“

See more on Altmetrics